selected letters 1996

Monday January 22nd ‘96

Dear C

I like the essay which I’ve read a couple of times: it does make good connections in relation to projection and introjection I think, and it is good for my ignorance to see a summary of the child-development positions laid out. To what extent there is a material connection between the personal and the institutional, and especially the national, concept, is something I want to consider longer. The models of psychogical individual development do seem to offer ways of examining what can be seen as insititutional or national behaviour, but I am uncertain of the bridge being other than metaphoric - in the way that mechanics and engineering are so often the basis for description of medical or physiological process. Maybe it can be precisely traced to the behaviour of individuals within the larger group: I only baulk at any model which in its own albeit heterogenious and multi-faceted way, might proceed by analogy to concretise a “we”, especially if suggested that that “we” is other than the accident of territory.

Perhaps I am straying off the path of your argument. Another reading, and preferably a good discussion sometime, will be welcome. About my own poems. The tea-time one I see as being an ironic thing about certain male-female positions in the West of Scotland, not themselves touching on religion. In fact it was yourself who alerted me to some of the basic ironies in the poem, years ago, that I hadn’t fully articulated to myself. The dependent/independent thing as discussed in “My Name is Tom” would I think be more accurately defined within the dependent/counterdependent poles of the Burns Conceptual Poem, Intimate Voices p 123. I can’t remember which analyst I read who gave me the “counterdependent” but I think dependence versus counterdependence more accurately describes the reaction formation into which the two halves have locked. Certainly (I suppose my Celtic-Rangers joke about Oedipus screwing his mother at both ends applies) a concomitant form of maturity would be required before a sense of independence could be achieved. In that I see, I think, a way of agreeing with the focus of your argument, as with the learning and accepting of differences - which I via Radical Renfrew tend to think of as a kind of structuralist dynamic of opposites.

Anyway Colin I will not rabbit on. I enclose a spare copy of a Lines Review from last year which had some of my new poems in it. You don’t need to find time to read them let alone comment upon them until whenever. But don’t put off contacting again “until you’ve read them”. That’s the sort of thing I do, and you’re not supposed to do it at all. I do add a strange wee almost prayer-like poem I wrote around the beginning of December, which calmed me down when I was feeling a bit uptight. Hope we’re in contact again soon.

Sunday March 3rd ‘96

Dear T

Thanks for the magazine. I’ll order the book itself locally in a bookshop.

The article does not contain the phrase which made me prick up my ears when used in the talk, which was something in respect of male “ontology”. I’m engaged in writing a long article about Crichton Smith, Edwin Morgan, W.S. Graham - for PN Review, ironically enough. Ontology comes into it, though mainly in respect of Graham’s structured relationship between author and reader, which I think of in terms of a kind of “transformational ontology”. The word has had particular significance for myself since coming on “ontological security” in RD Laing’s The Divided Self of the mid-sixties. In my own mind though it has a kind of relationship with Duns Scotus’s haeccitas. The nature of the Present Tense.

Where people’s ontologies seem to being criticised in the plural therefore I want to get a stethoscope out and have a listen to the health of the language being used. I know about the argument that if the unconscious is structured like a language, and the language is rotten, then you have people limited by rotten (un)consciousnesses. But those be dangerous waters of collective dehumanisation sailed of course by every imperialist since colonisation began, and not to be unmuddied by a reaction formation. At any rate I want to see the precise text of the lecture. Her poetry in translation - I can’t read Irish - such as Heaney’s translation “Miracle Grass”, I think wonderful.

Enclosed is a spare copy of the Lines Review in which I had some poems last autumn. It was good last year to be writing poetry again after a gap of a few years where my writing seemed to go into other shapes. In respect of the shaping, I love Carol Rumens definition of the essence of a poem as “silence used as a major part of a rhythmic structure”. That’s as near to the heart of it as I’ve seen in print. Also, that the gender of the poets from whom you learn is “not nearly as important as how they use the word “and”, or whether they put a comma between two adjectives.”

Tuesday March 27th ‘96

Dear S

Thanks for the card, and your letter. I have thought of you and C a number of times, though as usual I am not very productive in the epistolary department.

Just now I wish I was more productive in the sense of getting some paid work, but that is not happening. The business of even signing on to get unemployment benefit is difficult under this wonderful government as who knows I might get a secret reading next week, or the week after, and obviously this would have tremendous repercussions on The Taxpayer, not to mention the Public Spending Borrowing Requirement, if persons of my persuasion were to get away with things. Still I am getting by alright in that area, enough of moaning. But this fucking government: they are now in the process of destroying the beef industry with their stupid deregulation of safety measures to please their pals in the feedstuff business; and yet they openly talk as if the main commensical question is whether slaughtering infected cattle on a large scale is feasible when it would have the effect of making the chancellor unable to give the promised tax cuts necessary before the next general election. They really are a bunch of corrupt bastards. Manufacturing here is being reduced to the status of putting together electronic lego kits for Japan, or making arms and fighter aeroplanes for Saudi Arabia.

At the moment I am busy putting together a long article - 5,000 words - on the poetry of W.S.Graham, Ian Crichton Smith, and Edwin Morgan. It is for PN Review, and I will send you it when it is done. Thanks for the postcard of the Duns Scotus. Your cards are always very sensitive, I’m really pleased to get the new one. I’ll just sign off now, enclosing the Lines Review of last autumn.

Monday April 8th ‘96

Dear Pauline Brown

Thanks for your letter. I didn’t know what you were talking about when you made mention of my “press release” until I remembered I had sent you the statement that went into the poetry magazine PN Review when they asked myself, and about 50 other poets, to send five poems with an accompanying statement about the work, for a special issue of the magazine. It was not of course a press release - I haven’t quite yet reached the stage of issuing press releases about the contents of my poems.

To your questions, some of which I don’t want to tackle as they are essentially about other people’s work, not my own. Which writers for instance have been influenced by my poetry is not something that concerns me in the act of writing. I have been thanked by some and that has been gratifying (when I have admired their work) but that is a side issue, nothing to do with my own work itself. Good writers like James Kelman and Irving Welsh choose their influences, I do not hold to a domino theory of Literature.

James Kelman has remarked his admiration for my “commitment to the voice”, which you will have seen quoted on the back of my Reports from the Present. But as he certainly knows, and intended, that commitment goes right throughout my work and is not restricted to the “obvious” voice presence of my Glasgow dialect sequences. It is certainly crucial in poems like “A Priest Came on at Merkland Street” and the sequence nora’s place. The whole politics of literature as a model of articulation as distinct from a model of layered meaning, and intrinsic value, is still too hot to handle in much of contemporary Britain—certainly in the groves of academe that lay claim to “teach” the stuff.

The crucial existential shift for me in my writing came against the background of my reading what can be called an existential tradition - Kierkegaard, the Hogg of the Confessions, Lermontov, Sartre’s nausea, RD Laing & numerous others - and the liberation gained from American, not British, certainly not Scottish, writers before me. I think it was cummings who first brought across to me that shift to the page-as-a-thing-itself. My reasons for admiring what was going on in America come out as clearly as I can make it in my essay on Williams in Intimate Voices. That also should answer your question about Eliot and the public voice. It relates to the point I make in the introduction to Radical Renfrew about the standardisation of language transcription in the nineteenth century. That again has to do with status of language, power, and who owns the Recognised Language that Supposedly Contains the World.

All this stuff is still about language as some kind of detachable thing from my work, and influence. That wearies me. I write poems, I am a poet, not a poser of linguistic conundra, nor a Writer of Scottish Literature. To understand my poems one has to understand a remark like Carol Rumens’s definition of poetry as “silence used as a major part of a rythmic structure”. One would have to know Olson’s Projective Verse essay, the work of Creeley, Williams of course, Zukofsky perhaps. At least, to talk intellligently about the work might require a knowledge of this, and say Beckett’s use of the comma in his great postwar prose novels, which knocked me out when I read them - aloud when pissed. Language as a model of articulation. Not some contribution to Scottish Language debates, like a covert letter to the Scotsman. Simply the given that Language is universal, though no single language is universal: the only universal language is art. I write my poems in the language of art. The writing includes as having equal weight, the spaces between the words and lines.

Why did I compose Radical Renfrew? Well, because it was there, as they say. The context I did explain in the introduction. I was glad when what surfaced, surfaced. It was a kind of paying homage to my ancestors, and bringing them back into the conversation from which they had been excluded. I just wanted to hear what they had to say, and to hell with their having to buy a ticket from some canon-holder to see if they could be let into the auditorium. I loved it, it was a privilege, and when recording some of the poems for Radio Scotland in a series based on the book, I brought into the studio a photograph of my great-grandparents that I had recently been given. It wasn’t a sentimental act, just a recognition: you don’t have to be “uncivilised”—or maybe you do—to perform the basic rite of honouring your ancestors. These things would be obvious in other cultures.

About “postmodernism” and whether I see myself as such. I think it’s a kind of truism that nobody knows how to define it, though in fairness much of the isms have that kind of aura, including the existentialism aforementioned. I mean nothing other than what I say in saying that I wouldn’t call myself a postmodernist, but if anyone wants to call me one, they’re welcome to it. I have been also called a structuralist, when that word was more in vogue. Whether or not the word applies, the business of simultaneity and collocation certainly is a feature of my work, obviously in something like “The Present Tense”, and also soundpoetry work like “My Name is Tom”, described in the essay “How I Became a Soundpoet”. I see this simultaneity as part of my artistic overall style, which I would like ideally to constitute a kind of republic of voices, grounded on a consistent personality and philosophy of language.

The Thomson book is as much a part of that as the others. The publishers messed up a crucial factor in printing out full the numbers I had entered numerically: this was because the central narration is intended as an information-dealing voice, that occasionally is pressured by the emotions of the “author”, and is always moving through a sea of quoted voices from the material. It reaches its furthest point for me in the diary chapter based on random numbers, with the use of the word “blank” when there was no diary entry for that date. That was nothing to do with postmodern tricksiness, as some thought, and was certainly further than the more patriarchal critics could go: it stood for me as the point where within the structure, the existence of the subject and the narrator were given the same weight. The subject could “escape” beyond the narrator’s definition. RD Laing is the kind of background to my thinking and feeling here.

But that to me is no more than what the arrangement of the Glasgow poems in sequences is about. The important thing for me about them is not whether they—and “Honest”— have influenced others: what matters to me is that they are “mobiles”, that the authorial voice is implanted on an equal footing with the described. The described voice is not presumed as Other, outwith the author-reader’s. But to me, I repeat, they are poems, first and foremost, and last.

To go back to your question about Radical Renfrew. Locality is important, I see it, in the way that Lawrence or Williams saw it. History through the five senses. Intimate Voices is for me a kind of statement that moves out into Radical Renfrew, then out again, through the person as subject, in Places of the Mind. The last poem in nora’s place and the first poem— “The Good Thief”—in Intimate Voices are really two poems about exactly the same thing.

Grassic Gibbon was a storyteller, which I am not. The process he describes in his quote is one employed by a story-teller before him whom I admire more than Gibbon, namely Galt. The business of so-called nonstandard English in my own work I think of as having at least as much in kin with a number of Caribbean and Afro-English writers as with any Scottish writer. It’s a pity that when The Late Show did a feature after Reports from the Present came out, they among other contributions about my work left a 15 minute interview with Linton Kwesi Johnston on the cutting room floor. But that’s politics. And locating the history of that politics you can go back at least to Wordsworth v Coleridge in the Preface to the Lyrical Ballads and Coleridge’s reply, Clare’s statements about grammar and use of same, Burns’s lowering of Milton’s register in the Address to the De’il. Thence to America for a while. It’s about status of language and not simply art, but status and worth of people’s individual separate existences. The stooshie over How Late it Was winning the Booker was simply because some found it hard to swallow that a high-status award was given to a work in what was seen as low-status language. When you refer to “the use of swearing”, ok Six Glasgow Poems is about 1967/68, Ghostie Men, which really goes into the register there, 1979. But “Cuntbittin crawdoun Kennedy, coward of kind” is from somewhere between 1490 and whenever Dunbar wrote “The Flyting” before his death. From the beginning of what’s recognised as modern literature, in other words.

Hope the above is

of some use. I envy you being in Barcelona, though the

temperature here has at long last crawled into double

figures.

Friday May 3rd ‘96

Dear Chloe Gill

Thanks for your letter. I’ll just reply here, answering by the numbers on your enclosed sheet as that will be easier for me on the machine.

1 It’s difficult for me to say what my picture of Glasgow was then, as I never really have a coherent picture anyway. It’s just the place I live in, and I consciously resist attempts that have been quite evident since the early eighties, to market it in different ways as a single-aspect high-status cultural object. This to my way of seeing things is simply a product of the prevailing monetarist culture of civic underfunding, which sees district councillors adopting the strategy of projecting themselves as Management Teams, aiming to attract revenue from tourists or external sources now known as “customers”. It’s all anathema to me I’m afraid, no doubt the planned giant needle in St Enoch’s Square will be the required new City Logo (like the Gateshead Angel) and the city coat of arms will one day be supplemented with a mission statement. Like Edinburgh and Liverpool supposedly “competing” with Glasgow for the City of Architecture award, and “we” supposed to be going to work with a spring in our step next day etc. when Glasgow got it. False notions of “loyalty” and a kind of bogus local nationalism are part of the Public Relations/ marketing hot air essential to it all.

In 1982 my family and myself had been decanted, to use the horrible metaphor (I prefer uprooted) while our house was being saved from falling down. Where we stay, and to where we returned about 1984, I like, as it’s a mixed studentish area facing a park. We’re very lucky. Lots of people in Glasgow are likewise or in different ways very lucky. Lots aren’t. It’s a city.

2. To be honest I haven’t a clue. If my memory serves me right there was subsequently a concern about financial shenanigans over the sale of the land in connection with the festival, but I have long since forgotten what all that was about. My only memory of the festival - I never visited the site - is seeing on TV Prince Charles trying to win natives’ favour by reciting some jeallie-piece nonsense at the opening. His accent was memorable: I think he pronounced “jammy scone” as “jammy skoon”.

3. It’s so difficult to separate jaunty newspaper stuff from actualities. The “public” is a concept anyway that is being replaced with “the customers”, see above. As a writer I feel glad about a deal of the things that have been going on in writing in Glasgow, but none of them are concerned with improving the city’s “image” for tourists. Or does “the public’s view of Glasgow” mean the citizens’? People like to think that others like them, and part of the drive, if for electoral as well as other reasons, has been to persuade citizens that tourists think their place is great. This has had to have been driven on despite enforced massive cuts in the rate support grant, ratecapping, and therefore onward cuts in civic funding. That is the nub that can’t be got away from.

But on the positive side, speaking as a citizen, the sandstone cleaning has done a lot to brighten the tenements up, there’s no question of that. There’s a generation growing up now to whom you would have to show photographs of the streets of blackened tenements everywhere for them to have a clue what the place actually used to look like not long ago. The cleaned buildings definitely lightens the spirit for people like me who live in such a sandstone tenement area.

4. I think I’ve probably answered this one as far as I can, when trying to work out answer three. Glasgow is like many former heavy industry manufacturing cities with no heavy industry anymore: there’s real problems about jobs. It’s in some ways simple as that I see it, in some ways complex. To what extent (and you can say this about much of Eastern Europe) are over-45 working class males to be flushed down the lav as having had their useful day; to what extent must working-class women and young people be brought on board a low-security, short-term-contract “service” culture with talk about ‘training”, “equality”, “no more dinosaur union tactics” etc - basically to provide the work base for a low wage free market economy? I do think unemployment and the effects of poverty have been heavily masked by the fact that Britain is still the tail-end of empire, and the destruction of the seamen’s unions has meant that cheap clothes and stuff have been able to come in from abroad. But again there’s complexities there too: you get areas of comparitively poor families where nonetheless there’s this kind of label-culture dependency, with kids who wear thin tee-shirts on cold days nonetheless getting some expensive label leather jacket, when that’s the peergroup thing.

I don’t know, and won’t pretend to know what the future is here. I’m lucky to be staying where I am, and I can see ok for the next couple of months, which is how I think a lot of people get by.

5. If

you’re still referring to the Garden Festival I

don’t know. I hope a lot of people had a good day

out. It has been ironic that the council has on the other

hand made sundry efforts since to commercialise bits of

the city parks, which always annoys me, and I have been

involved in more than one campaign to stop them turning

Kelvingrove Park into either a three storey entertainment

complex or a huge Gallery of Scottish Art. Thankfully both

these have been beaten off so far, though the latest plan

is to uproot lots of it to drive “a light railway

system” through. The battle continues. All the best.

Wednesday May 15th ‘96

Dear Tessa (Ransford)

Thanks for your generosity again, which always lifts my spirits. I hope I never presume on it.

How exciting to see the name of Alex Neish in print. Is this the Alex Neish of Jabberwock and Sidewalk? I have wondered what happened to him, and what he did since then. Of course unrecognised by the Scotlit mortuary departments, since what he did with these is still alive, and issuing death certificates. What a great short essay, MacDiarmid’s “America’s Example to Scottish Writers”, welcoming the enclosed Olson, Creeley, Ginsberg et al to Scotland - in 1959, for heaven’s sake.

Maybe Alex Neish has been visible and I have as usual been myopic. I’d like to know.

Hope you enjoy the

enclosed Lite Bite.

Sunday May 19th

‘96

Dear Charles King

I trust you both enjoyed Ireland. Pity the weather isn’t a bit warmer, I do feel sorry for some of the tourists in Glasgow just now, today seems colder than ever, about 10 degrees, raining and a bloody cold wind. But it wasn’t so bad overall when you were across the water I think.

Enclosed is a piece I wrote for the STUC magazine about the small library in TUC headquarters down here. The piece is not in any sense a lively piece of writing, merely an inventory of some of the things in their collection. But I wanted to draw the existence of the library to the attention of the many who know nothing about it, so I thought a kind of listed sampler would raise people’s awareness and perhaps curiosity to investigate further. The editors chose the title (I had “Keeping the Red Flag Flying” - perhaps a bit extreme in these New Britain days when the flag is supposed to be in the Dinosaurs’ Department at the Party Museum) and I suggested that “socialist activist” might be a bit farfetched, some unsympathetic acquaintances might rather see me described as a hard-left couch potato. But they printed what they chose, so there it is.

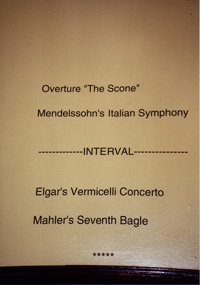

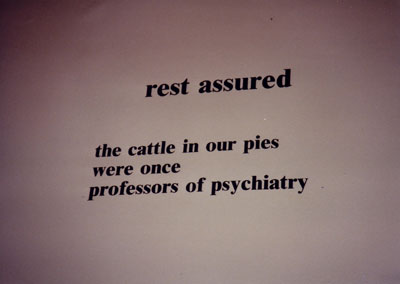

In recent weeks I have been working towards a small exhibition of texts I was asked to do along with some other writers and artists in the Pearce Institute in Govan, really a local community centre now. The space chosen for my own pieces was the restaurant, a pie & beans, fish & chips place really. I had a laugh drawing these things up, they’ll be enlarged in the same font and put directly on the walls.

Also enclosed is a tape purchased for £1 from Bargain Books, Clemens Krauss conducting the Strauss family. I always thought his Strauss was superb, it was played often to me by a friend when the performances were on Ace of Clubs in the early sixties. The recordings here and there show their age, but are well worth belting out when some lifting of spirits is required.

[Two of the Foodies posters stencilled on the wall of the

canteen. The "mad cow" beef disease was prevalent at the

time.]

Monday June 17th ‘96

Dear Sally Banks

Thank you for your letter of the 3rd. I would have replied sooner but a bout of flu messed up my schedule for things, which got left behind.

It had actually occurred to me looking through my BBC work for the year that perhaps you did in fact use for The Afternoon Shift the recording I had made myself for another programme. I’m glad to learn that that was the case, and I have no objection to your having done that.

The reason I was so alarmed at first is simply that I have had some really awful experiences of people using my dialect poems and assuming I would not disapprove. In fact without exception even the best-intentioned actor/reader has noticeably “put on a Glasgow voice” for the poems - even when they have had a natural Glasgow accent of their own to begin with. The results have been the exact opposite of what the poems intend. That’s why, however hypersensitive it might be thought, I’ve just had to really make an absolute rule - only myself gets reading them on the radio and tv.

Anyway it’s been cleared up satisfactorily this time. Thanks again for writing.

Thursday August 15th ‘96

Dear S

Here is the sequence newly finished that I told you about on the phone. It is largely extracted from a lot of material tidied up that I wrote for a performance one man stage work I was commissioned to do for the Third Eye centre a few years ago. Also there were some poems written in a notebook that otherwise contains BV Thomson material. It’s a good job I rescued it as in a few weeks the notebook and all my other Thomson workings are going to the Glasgow University Special Collections Department. I’ve managed to sell them my Thomson stuff for a couple of thousand pounds. Much needed dough as I’ve nothing much else coming in.

We enjoyed our week away in England, the cliff walks as I mentioned were terrific: the Cleveden Way runs I don’t know how far along the Yorkshire coastline—a couple of hundred miles I think.

I’m off to England again next week, this time to teach an Arvon creative writing course in Devon, right down at the back of beyond. Anne Stevenson will be my fellow tutor, and the pupils are some sixth form college. When I’ve took an Arvon before the students have been adult, so this will be a bit different. Kathleen Jamie should have been the tutor along with me, but she had to call off as it was going to be difficult with her new baby. The train journey from Glasgow itself is seven and a half hours, plus a long lift by car at the end. She would have been coming down from Fife. Anne Stevenson and I come from very different poetry bases, but I used to know her when she was in Glasgow (living with Philip Hobsbaum in the seventies) and she is fine to get along with.

Don’t worry about writing for a while, you told me you’re busy and anyway usually it’s been yourself sending long letters into a Scottish silence. Hope you like the sequence: I’m quite happy about it, haven’t decided yet whether to try to get it published separately as a booklet, which I do think I’d quite like, or with my other new stuff of this past couple of years. I add a few of the poem phrases that you might otherwise have difficulty with.

All the best to C and yourself. Next time you are coming to Scotland don’t worry about looking for a place to stay this time, assume you can stay at Eldon Street, you will both be very welcome.

Friday September 27th ‘96

Dear

I’m sorry I can’t sign the form as printed, despite my total opposition to the nuclear arms business.

I can’t take part in a formal address to members of parliament which gives their position a dignity it does not have. They’re certainly not my “representatives”.

I will consider them to be worthy of address when they show any interest at all in such items as, for example, the hundreds of thousands of children who have died in Iraq because of British imposed sanctions; the British backed billions of IMF money that has funded the carnage in Chechnya; the expensive provision of British arms, bombs and warplanes to further the American-German-Croatian axis in central Europe; and the complicit backing by Britain of America’s crucial role in the oppression of the Palestinian people.

You’re welcome to use my name as one of those totally opposed to Trident and to nuclear weapons, as signed in the enclosed. But not in some “mandate” to the Westminster mob.

Sunday November

17th ‘96

Dear Anne

At last writing to

thank you for your letter and book—it has been

ignorant of me not to have got back to you before now.

There was a flu, there was the busiest three weeks

I’ve had this past two years (doing readings with

Edward Dorn and running another non-Arvon creative writing

thing) but really it was that I hadn’t got down to

reading your biography of Plath and wanted to do so before

writing. I’ve read it now, an important book it is

of course, compulsive to read, and I’m glad you put

it my way.

It’s set me

thinking about the nature of this writing beastie and what

way it grabs our throats or ankles. The Plath of two

opposing selves seems a convincing presentation, the

ontological mess in the spotless kitchen, the girl who had

to win the Ideal Home competition along with the Great

Poetry one. A pity great poetry had to be sought in the Id

and the Ideal Home in the Superego. Or something like

that.

And yet.

I’ve never been satisfied with Plath’s

position as it came to me certainly in the late poems.

There has always seemed to me a complicity being asked, a

double-bind that indeed as your book brings out gives

specific and demanding weight to the phrase “special

pleading”—while at the same time taking refuge

on a ground note reiterating the one phrase: Fuck You. And

how I hate that Holocaust imagery, as if Auschwitsch can

be reduced to a purely metaphoric level—in order to

be transmuted into the ultimate soapy dish to be hurled at

the door. It’s a kind of parthian, grandly inflated

particularism that can only be a universal if all daddies

are basically bastards and crypto-nazis, which of course

some folk are very happy to believe: they must have been

very upset indeed by your book. Whaur’s yer

triumphalist victimology noo?

The whole social

area that you deal with I find tremendously interesting,

that really hardedged competitiveness, the sense of

striving to be amongst some kind of heritage-elite, makers

of value in the central narration. It’s fascinating

to me, like watching some kind of queer beehive under

discussion. And they really believe it. That comes over

very well: how naff, how absolutely fucking naff, to move

into Yeats’s house. Gradus ad Parnassum.

And yet, again. Plath comes out quite sympathetically, as sympathetically at any rate as the credible, and the quotes from her, especially I thought in the prose, just flare up in the page as damned good writing. Which is the point. I think what our biographies share is a decision to make the author responsible as a person in relation to the subject. In mine it is largely implicit until the end, in yours it is explicit. We do it from different poles but it is there. They’re both books by poets about poets, people as beings in the world resolving their position with another late member of the family.

-----

I’m

sorry I’ve taken this time to get back. It’s

now the 27th, and half six in the morning. I decided to

get out the bed this time, instead of lying looking at the

ceiling, wondering where the hell the Boat of Life is

going now. The trouble with being married sometimes is

it’s too comfortable, the bed’s too warm and

you tell yourself you don’t want to wake your

partner by making a noise getting up. And you can’t

put the light on to read. Maybe it’s just central

heating we need.

Which makes me

think, again about your book. How much competitiveness

there must have been between Hughes and Plath; I just

don’t believe it wasn’t there under the

surface, and a crucial feed-in to the last outburst. But

the myth of its absence must have been wonderful: the

whole Yaddo episode reads as an idyll of becoming, I

really enjoyed that, and of course it has its structural

place in the story.

For another story

I happen to have read recently about an artist, I

recommend very strongly The Early Life of James MacBey.

It’s a short posthumous memoir in the recently

remaindered Canongate Classics, and is a remarkable book

describing the childhood and coming of age of an etcher in

a grim anti-artistic Aberdeenshire culture at the turn of

the century. Alasdair Gray read it and bought half a dozen

for friends. I can well see why and will send you one if I

come on another.

Thanks also for

Four and a Half Dancing Men. It’s strange reading it

how one of the first people to come to my mind was me old

friend Williams, whom I normally don’t bracket with

your own prosody. But Salter’s Gate took me right

away to that road to the contagious hospital, the rhythm,

the “pointing out /come discovery” of clear

visual specifics in an “ordinary” location, as

revealing somehow the meaning of the place, located out of

the way of places-supposedly-having-meaning. So American,

Puritan maybe, like the wonderful Hopper watercolours I

could have taken off the wall and ate at an exhibition

last summer in the National Gallery in Edinburgh. Of

course not exclusively American.

How Brueghel

attracts the poets, almost to a point of their own

definition as artists sometimes, or to some reflection on

aesthetics in relation to the real world. Your own

Brueghel poem I like the way it connects with one of the

book’s carrying subtexts, it seems to me, about the

creative act: in relation to which the image of the title

poem of the collection is beautiful when discovered in the

poem itself. It takes me, the child in the bed with the

valley of the blanket from the knees, not only back to my

own childhood as one of those “basic images”,

but to Winnicott, whose writing on creativity I find very

exciting: it is Winnicott’s “potential

space”, where in creativity the “transitional

object” is for the child “the root of

symbolism in time”. Do you know Winnicott’s

Playing and Reality? “It is in playing and only in

playing that the individual child or adult is able to be

creative and to use the whole personality, and it is only

in being creative that the individual discovers the

self.”

Anyway there is a

great deal in your own collection that I admire and enjoy

very much. Thanks. Here’s a copy of Radical Renfrew

for you to enjoy some of at any rate I hope, perhaps to

argue with some too. Marion Bernstein and Edward Polin are

amongst those I think worth a first look, though poets

like Inspector Aitken (that’s right) show a lot of

skill and feeling in something like “After the

Accident”.

Don’t reply if you’re too busy, I hardly deserve it. See you next year at Arvon.

Monday November 18th ‘96

Dear Charles

Your letter begins

by saying that you’re worried in case you have

offended me. Charles that is simply not possible and never

will be possible. I trust your friendship and good wishes

absolutely and believe me they are entirely reciprocated.

However I have been remiss lately in fact we both have

been a bit remiss over this past couple of years in not

keeping as regular contact as before. A visit from you

next time in Glasgow would remedy that in the best way.

I’m sending

a letter rather than phoning as I owe you a letter and

sometimes a letter’s better. We can speak by phone

tomorrow or the next day. I did phone the day I received

your CD, for which much thanks, but there was no answer or

the line was engaged, I think the former. Of course I

should have kept trying but I did honestly phone once so

maybe you will let me off with a hundred lines rather than

six of the belt. Or maybe you’re really annoyed and

will send me The Three Tenors.

Part of the reason I’ve been behind with things in this past month specifically is that the end of October and the beginning of November seem to be for some reason, this past few years, that period of the year when I am run off my feet with readings and other commitments. It must be something to do with Winter budgets. Not that I mind earning the money at all, but it is strange the way things seem to pile up at this time. I’m just now at last relaxing after a three week period in which besides school readings, I was in London one weekend for two readings, then cutting in and out of a tour with the American poet Ed Dorn which meant readings in Preston and Swansea as well as Edinburgh; also a creative writing weekend with Kathy Galloway at Wiston Lodge, the YMCA place down past Biggar. That last was an absorbing weekend: apart from my being reminded how dark darkness is and how silent silence is in the country, there was an interesting mix of students at Wiston. One half was from a Lanark writers’ group, earnest people, a few quite poash; the other half was from groups associated with the magazine The Big Issue —not poash at all, in fact tending more to the pissed.

It was a good

laugh actually and there was some good work done.

I needed a rest after the back-to-back carry-on of different things. The organiser of Ed Dorn’s tour had billeted him with me for three days as Dorn wanted to see Glasgow. I’d never met the man in my life—though I’ve admired his magnum opus Gunslinger for years—and although he was agreeable company in many ways I found his presence, catechising me all the time for what proved to be a journal of his visit that he was keeping, to be a great strain. Things are a lot quieter again; I’ve managed to keep my financial end up besides readings by among other things selling manuscripts. The Places of the Mind manuscripts and related documents, all 62 cardboard wallets of it,

I have sold to Glasgow University Library. There’s a guide that I drew up if you want a copy. I’m also selling bits and pieces to the National LIbrary though I don’t expect much dough from that. But bits and bobs keep coming along, and it keeps me earning certainly more than I would if I was signing on. This morning’s post has a request for me to do the entries of the new DNB for Motherwell and Tannahill.…

I presume you have read The Early Life of James McBey which I have just read there this weekend. What a wonderful book. I was given it by Alasdair Gray who, when he read it having bought it as a remaindered Canongate Classic, went back and bought another half dozen to give to his friends. It is the kind of book that would make you do that. Quite a foil to the life of Sylvia Plath which I have also recently read in the biography by Anne Stevenson, with whom I did an Arvon a couple of months ago. More on this when we talk.

Wednesday November

20th ‘96

Dear Mrs C

Thanks for the

proofs and the letter. Regarding the proofs, there are

just two things I’ve added to Merkland Street: that

there be a bit more space between the subtitle and the

text, and that the closing envoi line be indented further

left than marked on the corrected proof sent.

In the

biographical/ interpretative paragraph, I have asked that

the first sentence be removed. It’s not simply a

difference of interpretation, it’s that the sentence

does not describe what my work is doing and will seriously

mislead readers of the anthology as to how to approach the

two poems. My phonetic Glasgow poems have nothing to do

with satire in the mode itself, rather the accurate

representation of a diction: satire may in some be used,

but it is in fact irony that is most likely to occur, in a

country where accent has such political significance

hierarchically. As for “A Priest Came on at Merkland

Street”, whatever the poem is about it is not about

“satirising the pretence and fraud in

institutions” through phonetics; it may be about

loneliness, its subtext may be something to do with

Kierkegaard, and its deliberately banal, low-register

implicit irony may be about distaste for Big Name bogus

high-register poems which pretend to write about Europe

and Western Civilisation breaking down when all that is

breaking down is the poet’s own humdrum self badly

in need of somebody to touch them and have some sex with

them. Anyway I don’t want that nailed to the mast

either, but please remove the flag that is

there—it’s not for my ships.

The other thing I

worry about especially in relation to this is the space

marked “artwork”. Do I understand by this some

kind of illustration? If so, then I’m sorry but I

can’t give permission for my work to be used until I

see what the illustration is. I have fallen foul of this

once before when an English magazine doing a special

“Scottish edition” printed facing some poems a

kiltie dancing arms in the air over a pair of crossed

fountain pens. I wouldn’t expect OUP to go in for

that sort of stuff but I would very much appreciate your

letting me know what this “artwork”

is—and sending me the proof if it is intended to be

illustrative.

Wednesday

November 27th ‘96

Dear Roxy

Have just read

your “Openings, Absences and Omissions” and

admire very much its clarity and usefulness. The sentence

“Once the customary narrative circuits are broken,

new chains of historical continuity begin to emerge”

is one of the heaviest marked, in the margin.

The debate between

culturalism and structuralism as between movement and

stasis of analytic position, moves closer to something

I’ve never yet been able really to tease out,

probably because I haven’t fully enough read the

sources or understood the theoretical debates when

I’ve tried. Certainly the subject as agent of

experience, as it were objectified in recording but

without moving away from the specifically personal, I will

not let go. I will not let the human in the Now somehow

slip off the board to be examined, and relegate the

ontological to the intersection of multiplex behaviour

patternings. What I understand as oppositional or binary

structures in analysis can be a useful road-digger into

asking questions about the past; but this only to throw

up—not discard— the points of ontology

revealed in the subjects that form the structure itself.

This at any rate is how I like to think of Radical

Renfrew.

My thought isn’t clear there I know. You have a capacity for lucidity that I could do with a bit more of myself. Here is the West of Scotland Friends of Palestine news-sheet that I mentioned I would send you. Sorry I haven’t done so before: the readings and other things I had in the weeks after we met (my busiest time for a good while) left me pretty knackered.

Thursday November

28th ‘96

Dear John

It was great to

see you again a few weeks ago. I’m only now getting

myself organised after what was my busiest spell for a

long while, not that I’m complaining about that. A

quiet spell ahead so I hope to get on with some more of my

own work.

Thanks for the

articles, your talk to the Dreaming the Homeland

conference and the essay for Neue Zurcher Zeitung.

They’re refreshing reading them again this morning

especially after hearing Gordon Brown in his supposed

budget “reply” last night make the now

habitual comment from the Labour side that they have no

intention in government of paying benefit “for

people to sit and home and do nothing.” This from

the erstwhile biographer of Jimmy Maxton.

I enclose among

other stuff the news-sheet I promised from the West of

Scotland Friends of Palestinians society. They send it out

about every two months. I’ll send you a copy each

time in future that I get it. Roxy has been sent one too.

His Openings, Absences and Omissions will help me towards

a clearer articulation, I hope, of the distinction between

culturalism and structuralism that he discusses.

It’s something I do keep coming back to without the

lucidity of organised reference of which Roxy is capable.

But it’s partly what Radical Renfrew is about I

think.

Of which I enclose

two bound copies, now that I’ve bought some up. The

paperback remains in print at £12. I’d be

grateful if you could pass on the signed one to Linton

when it’s convenient. The other one I have not

signed to you as you have a signed paperback (I presume at

any rate, my memory is duff these days) and you might want

to pass it on or whatever. All the best John I hope your

health continues to improve.

Tuesday December

10th ‘96

Dear Calum

Enclosed is

Kavanagh’s “If Every You Go to Dublin

Town” which seems to be the poem you’re

looking for. I think your friend probably remembered

something being said about Kavanagh’s bench in

Dublin: he liked walking by the canal and wrote a poem

about a commemorative bench there. (It’s that

penchant in Dublin for revered literary landmarks,

Kavanagh’s bench, McDaid’s etc that I

satirised in a little squib “Dublin” in

Intimate Voices.)

I enclose also a photo and a couple of other poems. The long poem “The Great Hunger” is his most sustained significant work, and one I think you would find worth reading. It’s really a polemic about religion and bachelordom in rural Ireland, giving the phrase of the title a more contemporary relevance than its usual reference to the potato famine of a century before the poem’s being written.