BV Thomson Chapter 2 rev

CHAPTER TWO

(1993 - updated Sep 2018)

The town of Port Glasgow had a population of about 6,000 people, which is to say about a sixth of the population of neighbouring Greenock - the largest sea-port in Scotland - about a mile west along the shore. Most of the ships entering or leaving Port Glasgow's 2 harbours traded with Glasgow city or other places on the Clyde; but an average of 7 vessels each month arrived from abroad - America, the West Indies, the East Indies, Canada, the Mediterranean. The main import was timber, almost 28,000 tons of it being imported in the year of Thomson's birth. Much of this was stored in large warehouses on the shore front, while other such warehouses held alcohol and refined sugar, both of which were prominent in the trade of the place. The sea dominated local industry, the main manufacturies being of rope, sail-cloth and canvas, whilst the town shipyards worked almost exclusively on the construction of the steamboats with which the Firth of Clyde had become internationally associated since Bells Comet of 1812.

Both sides of the newborn child's family lived in Port Glasgow. His mother was the daughter of Margaret Lawson, one of the town's 4 midwives; Margaret had been twice married and twice widowed. Her first marriage was in Edinburgh in 1791 to a George Parker by whom she had a son John. Then on 18th August 1798 Sarah was born - in Blantyre - "daughter natural to Alexander Kennedy soldier in Lochaber Regiment and Margaret Lawson College Parish Glasgow". The parents did not marry until five years later in the Gaelic Chapel, Glasgow, in September 1803, when her father Alexander was entered as a “sawer”. Their second daughter Margaret was born in 1806.

Sarah Kennedy's own marriage took place at St Ann's, Limehouse, London, on January 12th, 1834. Her husband James Thompson was a merchant seaman 8 years younger than herself. Born in Logierait near Pitlochry in Perhshire, in 1806, he alone in his family adopted the English spelling "Thompson" as his surname on his marriage and work documents. His father John Thomson (no "p") had worked as a weaver and small farmer at Logierarit before moving south to the Firth of Clyde with his wife Helen and their family of 6: Lillian (1799), Ann (1802), Charles (1804), James (1806), twins Susan and Helen (1808), and John (1811). A seventh child, Mary, had been then born in Port Glasgow in 1817. The second oldest, Ann, was she to whom Sarah Kennedy wrote the millenialist letter of 1831.

In Port Glasgow the 7-strong family of Helen and James had been poor: some of the children slept in a trunk on the floor, a fact some townsfolk reputedly liked to recall with mischief when Helen in later years as Mrs McLarty was owner and director of a sailcloth manufactory, and lived in a large house at Clune Park on the edge of the town.

Church Street runs down to Port Glasgow harbour, and at its corner with Princes Street stood the house later claimed as where Sarah gave birth. The parish register entry of birth does not give the address, but simply reads "James Thomson mariner and Sarah Kennedy his spouse had a lawful son born 23rd Nov 1834 Bapt. 28 Feb 1835. Called James." The entry was not made though until May 1848, 6 months before the boy's 14th birthday, and the spelling of the surname reflects the change from "Thompson" to "Thomson" as amended by the boy's school in London.

In matters religious the "gift of tongues" ceased soon after 1834 to be a matter of public debate and scandal. George and James MacDonald both died in 1835, and the MacDonalds' small circle of adherents made no more public noise. One of their followers regretted in a memorial biography that the power of the Holy Spirit had withdrawn locally "into the retirement of the closet, or the circle of the few who alone have cherished it". Like the MacDonalds themselves the author thought Irving's congregation had been led astray by "men assuming the apostleship, and, by making the voice of the prophets subordinate to their superior office, gradually suppressing it."

Seaman James Thompson worked in vessels registered at Greenock and Glasgow. In September 1836 he was enlisted for a few months on the new Glasgow registered Mountaineer, built with intention to trade to the British colony of Demarara in Guiana. Two of the Mountaineer’s three owners lived locally in Scotland, the third, Thomas Wilson, was in Demerara itself. Slaves in the sugar plantations there and throughout the British colonies had been freed by the abolition of slavery in 1834. But until 1838 they were still held in what was officially called an “apprenticeship”. Ship building on the Clyde was an integral part of trade built on slavery in the colonies. Sugar and its refinement was part of this.

Port Glasgow was described by the local minister in 1839 for the forthcoming Statistical Account of Scotland thus: "In its general appearance the town presents an aspect of neatness and regularity, not often to be met with. The streets are straight, and for the most part cross each other at right angles; while the houses, pretty nearly equal in size, and generally white-washed, give to the whole a light and uniform appearance." The view from the hill overlooking Port Glasgow and the Firth he thought "not surpassed in grandeur and loveliness even by the most admired scenes of which England, and perhaps even Europe, can boast." There was poverty. A soup kitchen gave out a quart of soup and a roll to each of the poor who had a ticket, and an average of 80 quarts were given out each day except Sunday - when it was shut. The soup kitchen had been launched partly "to check intemperance among the poor", and intemperance was one thing the minister thought needed checking:

In the year 1790, with a population of 4,000, there were no less than 81 public houses in the town. It is gratifying to be able to state, that in March 1835, and with a population of about 6,000, the number of public houses had been reduced to 70. It would still be more gratifying to be able to add, that the practice of intemperance has diminished in the same proportion. Appearances, however, do not by any means warrant such a conclusion, and seem to indicate, that intemperance never prevailed among the lower classes of society to a wider and more alarming extent than in the present day.

But by the time this report was written, Sarah and the family were removed to London. The Mountaineer had re-registered there in 1837. But when James Thompson enlisted as First Mate on a vessel in London in June 1837 it was not on the Mountaineer bound for Demarara, but on another distant merchant trader— the 423-ton Eliza Stewart bound for China. This was to be first of three such voyages Thompson made between 1837 and 1840.

In October 8th 1837, three months after he had left on the first of the voyages, a 10-month old infant daughter was baptised in Newman Street Church - the same church where Irving had been preaching as "angel" before his death. The infant was called Jane Bowler Thompson, and the entry adds simply that the date of birth was November 26th the previous year,1836. She had been born 3 days after her brother James's second birthday. Their father James Thompson was only with his family for 2 short stays between his three voyages to and from China: a month between May and June 1838, and 6 weeks between June and July 1839. While he was at sea a few months into his third voyage to China, the infant Jane caught measles from her brother James, and she died. She was buried in London in October 1839 shortly before her third, and James's fifth, birthday. It was fully another 11 months before their father returned to London; and when he arrived he did so paralysed down his right side, having suffered a stroke while at sea. Sarah had become her husband and the boy James's sole source of support. At this point, according to a sometimes confused family account written in 1934 by a granddaughter of Sarah’s sister Margaret, money was sent from Port Glasgow by Sarah’s mother. The family account has it that the money was to train her as a court dressmaker.

Though Port Glasgow had its poverty and poor housing, the east end of London presented poverty and poor housing on a much larger and more intense scale. The district of St Mary's in the parish of St-Georges-in-the-East where the family were settled and where the infant Jane was buried in 1839, was the subject of a pioneering economic and social analysis five years later in 1844. The parish did not show London poverty at its worst, having been chosen for analysis as "an example of the average condition of the poorer classes of the metropolis," which meant it was "a population entirely above the wretched system of sub-letting corners of the same room". Nonetheless as an averagely poor district it was "one of those composed of dingy streets, of houses of small dimensions and moderate elevation, very closely packed in ill-ventilated streets and courts, such as are commonly inhabited by the working classes of the east end". Mary Ann Street, where the Thompsons lived in 1842, was a street of 2- storey houses in a warren of streets midway between Commercial Street and Cable Street, not far from St Katherine Docks. It was 100 yards long, 9 yards wide, and described in the 1844 assessment as "well paved", "well lit", with "good" drainage and a "plentiful" water supply. However, "good" drains meant "good and clean surface drains"; and a "plentiful" supply of water was one that was "a plentiful supply three times a week" - for 2 hours at a time. Other streets in the surrounding area were worse off: "In many parts of St Georges in the East there is no drainage, and the kitchens, in some places, after heavy rains are stated to be several inches under water; which, when it recedes, leaves an accumulation of filth and dirt of the worst description." However even "good" surface drains as in Mary Ann Street were not good enough for public health in the absence of a continuous supply of water to clean them. This was recognised at the time:

But even supposing that all the houses had drains, and all the streets sewers, and that they had been properly constructed, so that they had the most approved form, diameter, and fall; still they would be in great measure useless, because they could not answer the purpose they were intended for, unless supplied with water: without a sufficient supply of water, to keep up a constant current flowing through the drain, the drain itself becomes positively injurious, generating and diffusing the very poison it was intended to prevent and remove.

The most common male employment in the district was labouring, and a sixth of that was in the nearby docks. In descending order of frequency there were shoemakers, gunsmiths, carpenters, sailors, then a wide variety of trades of all sorts down to "ginger-beer-seller", "chair bottomer", and "house of ill fame." No details about the latter were entered upon, though the report on St Mary's District where the Thompsons lived, noted "at least 50" houses of prostitution. Attention was drawn to the problems caused by women's low pay, especially when the women were supporting families on their own: "we find much greater diversity of age, with very limited means, derived from the narrow range of employments for female hands, especially if unaccompanied by a vigorous frame and habits of bodily exertion. The extent of such employments, as compared with the number of struggling competitors for them, being always limited, their renumeration is low. The relative superiority of men's earnings over those of women, and even more over those of the women and children combined, in the metropolis, as compared with most of the manufacturing districts, is thus very conspicuously shown." The average rent in the district was "no less than 3/7d a week" in 1844. A needlewoman could earn about 5/9d, though a court dressmaker, as distinct from an ordinary dressmaker, could hope to earn up to 17/-.

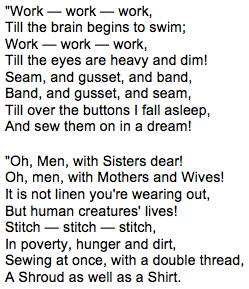

The work took a terrible toll on women's health, as reports increasingly indicated. "No slavery is worse than the dressmaker's in London" one woman told a government inspector in 1843. Before the invention and patenting of the sewing machine it was a job which used up young women like Kate on her way early to work in Dickens's Nicholas Nickleby: "At this early hour many sickly girls, whose business, like that of the poor worm, is to produce with patient toil the finery that bedecks the thoughtless and the luxurious, traverse our streets, making towards the scene of their daily labour, and catching, as if by stealth, the only gasp of wholesome air and glimpse of sunlight, which cheers their monotonous existence during the long train of hours that make a working day."

Hood's "Song of the Shirt" became famous in 1843. That was to be the year of Sarah Thompson's death.

For those trying to do the court dressmaking which payed more, there were the two busy "seasons", from April till the end of July, and from October until Christmas. But by the end of 1841 Mrs Thompson was in advanced pregnancy, and on the 4th of February 1842 she gave birth at 24 Mary Ann Street to another boy, whom she called John Parker Thompson after her late step-brother. She became ill, and sought help for her family. It was now that her connections with the prosperous Irvingite network came to some use.

Regent Square Church was still the official place of worship for the boys of the Royal Caledonian Asylum in Islington; an asylum "for the maintenance and education of the children of soldiers sailors & marines, natives of Scotland, who have died or been disabled in the service of their country, and of indigent Scotch parents, resident in London, not entitled to parochial relief." The Thompsons were now such parents, and application was made to have James taken in. Boys were admitted at the age of 8, and James would reach his 8th birthday on November 23rd that year.

The Caledonian Asylum was a favourite charity of London-Scottish aristocracy and well-to-do. Fundraising balls and dinners were annual events, at which the boys who were the object of the charitable donations would be ceremonially marched round the room before their benefactors. These gala events were an integral part of the court calendar which court-dressmakers such as Mrs Thompson would labour to dress. The annual summer fancy dress ball in Willie's Rooms in 1842 was attended, The Times reported, by between eight and nine hundred:

...a vast number of whom appeared in the rich and picturesque costumes worn at the Queen's Masque. The rooms perhaps never presented a more brilliant assemblage of rank and beauty. The boys of the Caledonian Asylum, attired in Highland kilts of the Royal tartan, preceded by the pipers of His Royal Highness the Duke of Sussex and the Duke of Sutherland, wearing the handsome Scotch mulls recently presented to them by command of Her Majesty, and attended by the officers of the institution, marched round the ball-room as usual, and were most warmly greeted. On returning to the ante-room they were inspected by His Grace the Duke of Wellington, who, in terms of great readiness and condescension, was pleased to express his admiration of their healthful appearance and martial demeanour.

There was competition for the small number of vacancies that became available in the Asylum every 6 months. An application had first to be sponsored by someone already on the list of subscribers to Asylum funds who had given 10 guineas or more as life subscription, or had annually given 2 guineas in subscription before the sponsorship. The approval of a prosperous backer with interest in the asylum had first to be obtained. Irvingite connections could help, as there were well off professional and even aristocratic members in the new post-Irving developing chuch. At Albury Mary Campbell, as Mrs Caird, had acted with her husband as sometime lay chaplain to Lady Olivia Sparrow; and when Mary came north to Port Glasgow on a visit in 1839 a year before her death in 1840, she travelled with Lady Drummond, which prompted the scorn of the minister Robert Story whose Peace in Believing had first publicised the religious fervour of Mary's late sister Isabella: "Look at any seamstress, labouring early and late for a miserable subsistence, and at your present condition, your very servant arrayed in silken attire... Where you are I know not, but of this I am persuaded, you are not where Isabella left you."

The seamstress Sarah Thompson and her disabled husband did manage to obtain sponsorship, that of a James Boyd, late of the Firth of Clyde and now co-director of a sugar-refining company in Breezer's Hill by London Dock. Once sponsored, an application was not thereby guaranteed success. Twice yearly the applications in hand were put to the vote of all the subscribers, the applications with the most votes then being matched with the small number of vacancies available. The application was endorsed with a statement of the family circumstances which the Thompsons then had witnessed by a magistrate, as required, at Lambeth Street Police Court Whitechapel on August 16th 1842. The application stated:

That the parents James Thompson born at Pitnacrea, Perthshire aged 37 years, Sarah Thompson born at Glasgow aged 42 years, reduced to poverty from the Father being incapable to follow his profession as a mariner in which he was actively employed as apprentice, seaman & mate and served in the following ships

CAROLINE Sep 1824 to Sep 1827

HALYARD Dec 1827 to May 1828

LEGUAN Aug 1828 to Nov 1828

MOUNT STEWART ELPHINSTONE Dec 1828 to Oct 1830

TAMARLANE Dec 1830 to Mar 1831

FORTUNE Apr 1831 to Jul 1831

HM SHIP SATELITE Jul 1831 to May 1832

GANGES May 1832 to Sep 1832

NAVARIN Oct 1832 to Jan 1834

JEAN Feb 1835 to May 1836

MOUNTAINEER Sep 1836 to Jan 1837

ELIZA STEWART Apr 1837 to Sep 1840

in which latter ship whilst chief officer he had the misfortune to be struck with paralysis which has totally deprived him of the use of his right side and rendered him quite incapable of earning his own subsistence and is dependent on the bounty of his friends and the exertions of his wife.

Has two children James Thompson the applicant for admission aged 7 years last November, John Parker Thompson aged six months. Your petitioner humbly prays, That the said James Thompson may be admitted into the Caledonian Asylum, and that he may continue therein as long as the Directors thereof shall think fit.

Sarah Thompson signed, but her husband, unable to sign because of his paralysis, entered a cross. The application joined another 24, only 8 of whom were to be successful that December. When the result of the subscribers' votes was declared at the next quarterly meeting the name "James Thompson" came 7th in the list of 8 successfully voted into a place.

Now seriously ill, Sarah on what was her deathbed sent for her sister Margaret to come to London. Though she now had four children including a new baby of her own, Margaret took the infant John Parker Thompson back to Port Glasgow to be brought up with her family. On December 1st 1842, six months before his mother's death in Mary Ann Street, the 8-year-old James Thompson, Registration No. 346, was admitted to the Royal Caledonian Asylum, Islington. On succeeding Sundays he now took his place amongst the 90 asylum boys "clad in the Royal Stewart tartan" who sat in the gallery of that same Regent Square Church from which, 10 years before, Edward Irving had been expelled.

BV Thomson Chapter 2 rev

BV Thomson Chapter 2 rev